Birthing anatomy includes soft tissues and hard bones.

Our bones are held together by flexible tendons, cartilage and ligaments. In pregnancy, the joints between the bones become more mobile. Waddling is an example of what happens when the leg and pelvic joints get softer. The baby passes through a mobile pelvis.

The hormone relaxin helps cartilage become more mobile. The muscles to the legs and pelvis are more effective when long and supple. Together the joints and muscles allow the pelvis to become a dynamic, flexible passageway.

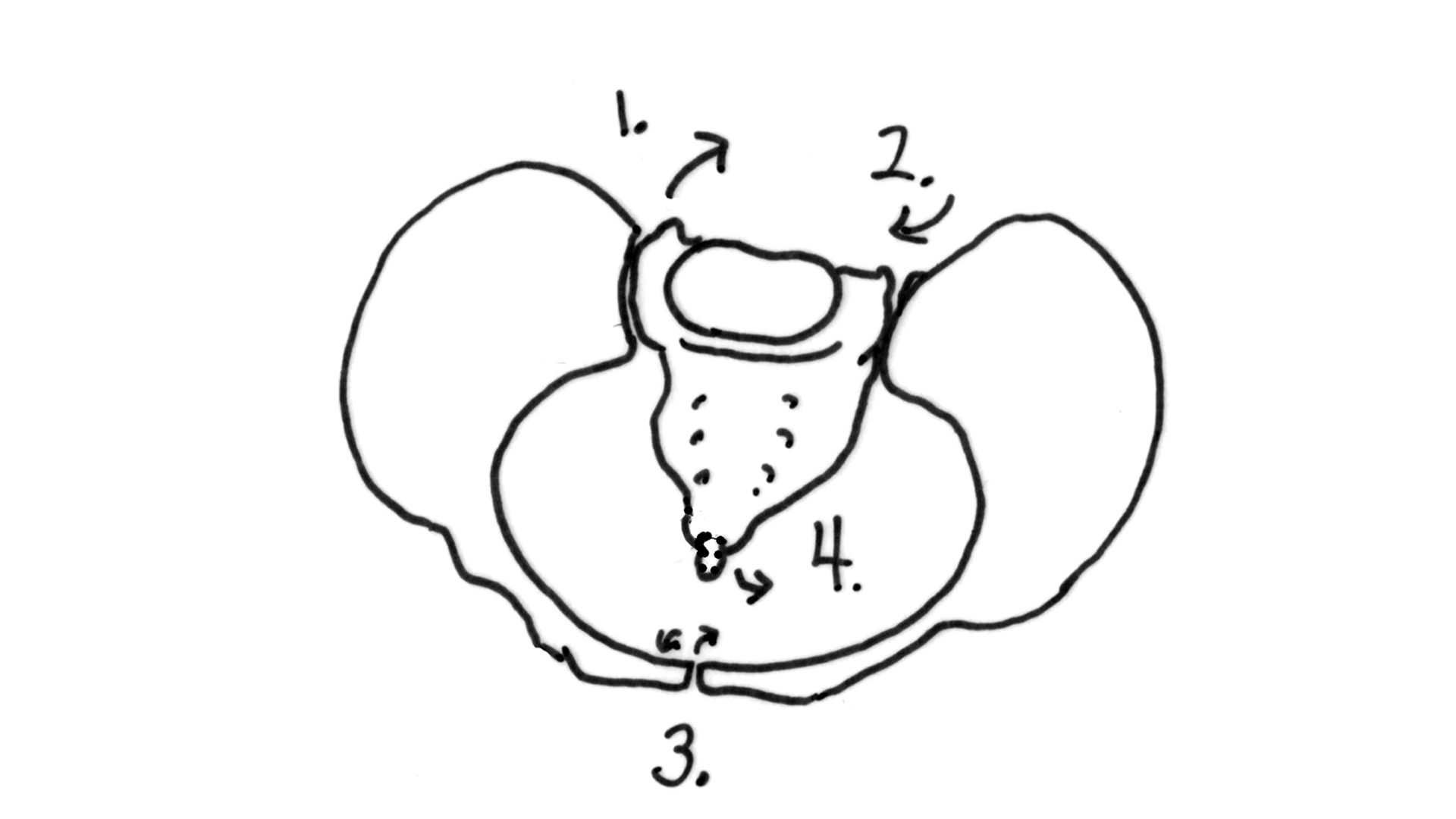

The bony pelvis has four joints. In the front of the pelvis is the symphysis pubis joint. Movement here really isn’t that comfortable. Sometimes a pregnancy belt holds this joint stable for walking and rolling over in bed. Symmetry in the symphysis pubis (pubic bone) reduces spasm in the round ligaments and helps the sacrum, around back, to be aligned properly.

On either side of the sacrum are the SI joints (Sacroiliac joints). These are located where the dimples are. Many plastic baby dolls have SI dimples above their bum. The SI joints are a common location for aches when the pelvis is weak or crooked.

Symmetry in the SI joints will help the sacrum be lined up with the pelvic brim. Then the baby can get into a nice, head down position. A chiropractic adjustment helps get the symphysis and the SI joints aligned.

The sacrum, rather than fused, is slightly mobile and in the birth process actually moves to allow the head past.

The tailbone is connected by a joint to the lower end of the sacrum. Sometimes this needs an adjustment, too, especially after birthing a baby. Ligaments connecting to the sacrum and tailbone (coccyx) will become more symmetrical and their tone will be more relaxed and less in spasm after bodywork on the pelvis.

The baby first passes into the brim when engaging in the pelvis. The angle of the baby’s head in relation to the brim of the pelvis plays a role in whether engagement is lengthy or more easy. Some babies engage before labor but when contractions get strong for a while and baby remains high at the brim, it may be because baby’s head is riding up on the brim or pressed against a portion of the inlet at an unfavorable angle.

When the bottom of the pelvis, the outlet, is more narrow than the top, labor can slow down here as well.

The good news is that the body is pliable, and muscles can be released, joints loosened, and fascia smoothed with simple and quick stretches or birth positions – when smartly chosen to match the need of the individuals birth.

Understanding inlet and outlet diameters can help match appropriate techniques and strategies for labor progress.

Why don’t I have Pelvic Types listed here?

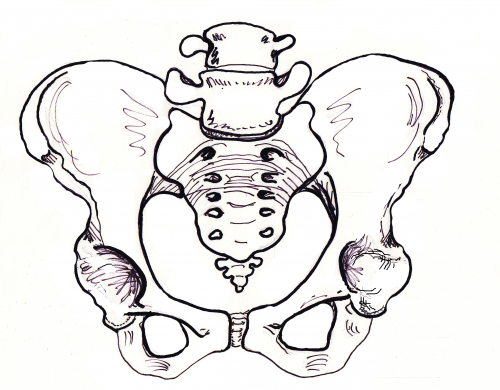

The pelvic passage for birth is made from the shape of the bones around 3-dimension space. The beginning (inlet), end (outlet) and mobility of the pelvis lets us divide the passage into three levels. Each level is associated with a shape and the shape of the inlet can vary from circle to oblong to triangle. There is less variation in outlet shape but outlet width or narrowness will play a role in childbirth.

Pelvic types are widely used in childbirth literature as typing pelvises was a way to organize the various shapes and other bony attributes of the human pelvis. Unfortunately, the doctors who published a widespread categorization of the female pelvis were raised and educated in our racially biased society and they attributed racist values to their pelvic typing. Later research showed a gross overgeneralization to separate the scattering of shapes into basically what was not called but easily inferred “white female,” “white male” and “black” pelvises. The names are gynecoid, android, and anthropoid.

Shaping is a result of nature, typing is a result of human interpretation. In other words, pelvises do have shapes, but categorizing them in “types” with values is based on human ideology around those values. “Pelvic types” is a human construct and on this topic has been typed in gender and racial ways that are not accurate, consistent or helpful, and have hurt people or lessened the quality of care some people receive, and limited care options, due to the categorization feeding racial inequity in the maternity system.

Kuliukas (2015). looked at 64 women and did not find a clustering of four types but a range throughout. The heavier, triangular pelvis did seem to appear with its unique characteristics, whereas there were many pelvises with a combination of round and oblong, or greater side-to-side and greater-front-to-back and everything in between without making two clear types of gynecoid or anthropoid.

Lia Betti of the UK offers a dynamic exposure of racist categorization of pelvis shapes and gives a re-interpretation of pelvic difference in Shaping birth: variation in the birth canal and the importance of inclusive obstetric care. For providers, pelvic understanding helps avoid poor technique among the slight differences in pelvic shape when forceps or ventouse are used. For providers and parents, noticing how the labor signals progress or a stall can help redirect care or choice of birth position so that that a position may chosen to optimize all the space available for the baby to move through the pelvis.

Pelvis width associated with bone mass distribution at the proximal femur in children 10–11 years old.

The variety of pelvic shapes, combined with the variety of fetal head presentations, plus size variations, mean that labors vary greatly. Engagement is the phase of labor most affected by pelvic type.

In the drawing, we see a round pelvic inlet shape and the correlating round shape of the pubic arch at the outlet.

The pelvic arch in front would allow three fingers to cover the urethra during a “potty dance” – the type of grabbing yourself and try not to pee your pants dance of a child waiting to get to the bathroom. Buttocks are round.

Hip size doesn’t indicate the roomy inside and a petite woman can birth a large baby. When the pelvic floor and other soft tissues aren’t overly tight, the birth tends to go well and a posterior baby can rotate at several various phases of labor.

A more triangular pubic arch may hang quite low, giving a fundal height reading higher than the compact bump may seem to justify. Closely-set, small buttock “muscles” of the android make small roundish or triangular cheeks to her “bottom.” The pelvis with a 2 finger arch, rather than the 3 finger width, means baby fits best with an anterior position and good flexion (chin tucking). Upright positions and more time for pushing and stronger pushing may be part of the story for some with a triangular brim.

Narrow in the front, this pelvis occasionally catches the posterior baby’s forehead. Back it up and let it turn!

Good fetal positioning, good flexibility in the pelvic joints, and balance in the soft tissues help the natural labor progress. The posterior baby will hope to rotate before engagement or may not be able to rotate until the head fully passes the pelvis rotating on the perineum. Manually rotating the baby’s head may be an option if a skilled doctor or midwife is present. A little help for the shoulders may be needed as the result of those women with low slung pubic bones. They may catch a shoulder.

Tall women with average size babies often birth without an issue even with a triangular pelvis but this shape is in noted in the medical literature for a higher rate of posteriors since babies can have a harder time rotating while their forehead is in between the narrower front shape of the triangular inlet and it’s corresponding narrower outlet. The triangular inlet will be more of an issue for shorter, older, or heavier bodies. Why a heavier body? Because of the correlation with weight and low thyroid and weight and posterior presentation (there is a correlation between low thyroid and posterior presentation). An advantage can be achieved by helping baby into the Left Occiput Anterior before fetal engagement.

A woman told me her doctor felt she may not be able to have a vaginal birth after she previously had a cesarean for birthing her first child. She asked me what I thought. While I acknowledge there are more challenges with a triangular pelvis for some of these labors, most births through an android pelvis are going to be able to finish by the woman’s own efforts –and her baby’s. I said:

Adding body balance and helping baby into position is extremely important when birthing with any smaller pelvis. Body balancing and birth positioning could make a positive solution for many in this situation. If the posterior baby can back up to turn to left occiput anterior and try again, there is much reason to expect a vaginal birth. To help the baby do this, Side-lying Release followed by an inversion of some type during a contraction or two can be necessary.

More important than shape is fetal position and more important than fetal position is the balanced joints and soft tissues of the pelvis. Particular crucial is the freedom of the sacrum to shift a tiny bit and to rise up in late labor.

Releasing the tuberosacral ligaments in the back of the pelvis is a way to allow the sacrum to have mobility and therefore, more space for baby. The sacrum moves out of baby’s way, as it were, just before the body begins spontaneous pushing. Our blog has two good descriptions of this release.

In this pelvis, the space for baby to enter is longer front-to-back and this spacing is true at the bottom, though baby may rotate a bit for the middle and then return to their starting position. The posterior baby fits more easily in this pelvis but babies are still usually anterior when they start labor. Either way, the Abdominal Lift and Tuck or a belly dance (figure 8 and front to back but not side to side moves) can be a help in helping baby get started into the pelvis (see instructions and what makes this work).

More posterior babies who are born vaginally may have the advantage of this pelvis’ longer front to back opening. Various vertical maternal positions and movements protect fetal engagement. Understanding the unique benefits of this pelvic type help birth finish by the mother’s own efforts.

The pubic arch is a wide 4 finger span what has been called the platypelloid pelvis, which is quite wide. Hips may seem wider side-to-side but mainly because the pelvis is flatter front to back. This allows for a flat (non-pregnant) belly look due to the short front-to-back distance of the bones.

At the bottom, the sitz bones are quite wide apart, more than the width of the person’s fist (if she can reach between them while lying down). Very few women have this situation but when a doctor spots it they may presuppose a cesarean is necessary. The best advantage for a vaginal birth is starting labor with baby in the Left Occiput Transverse position where baby is facing sideways. Body balancing can help baby get settled this way, but not simply gravity. Go for an broad and inclusive approach to body preparation, not strength but length in the muscles and more importantly, balance!

Baby really needs to be in the LOT position to get INTO the pelvic brim for engagement. Long early labor is common, but if the baby isn’t LOT, the two days of labor will be all about getting baby rotated and strong contractions and mobility are essential. Once the baby is into the pelvis labor tends to move along, within 5-8 hours of engagement. Pushing may not be very long because the outlet of the pelvis is large. Using Daily Essentials: Activities for Pregnancy Comfort & Easier Childbirth, and Spinning Babies® Parent Class may help your baby get into a LOT or other ideal position.

Pelvic cavities can have a MIX of opening or closing shapes

How to fit the pelvic shape into a label or category is less important to practice than having a set of skills to identify the relationship between the long axis of baby’s head with the short distance of the pelvic level where baby waits during a labor stall. This means, you may use a set of skills for helping babies through a diameter of the pelvis with a particular shape.

Knowing what is going on between the baby and the mother at the inlet or other diameters of the pelvis and what we can do to help when help is indeed appropriate. This is explained in the low-cost download, Spinning Babies® Quick Reference.

Occasionally a pelvic shape sets the fetal position. But this, I believe, is secondary to soft tissue “balance.” Some pelvises don’t accommodate posterior presentations. The baby must rotate or will not drop into the pelvis. When the mother can re-angle her pelvis to let the baby in (See steep inlet in Is baby engaged?). A birth stool, posterior pelvic tilt, and standing and leaning over a dresser feels right.

Rarely, a pelvis is too small to let the baby enter the pelvis. When a pelvis is too small its called CephaloPelvic Disproportion (CPD, or baby’s too big). Rickets, injury or an actually too-big-baby may be the cause here. CPD is rare but does exist.

Before we suspect CPD in pregnancy, check to see if the baby is engaged. Until the baby is LOA or LOT and in one of those ideal starting positions, it’s too soon to call it CPD. We have an article on this called Will baby fit?

The tone and relative symmetry of a woman’s uterine ligaments and muscles either makes room for baby or reduces room, if tight and twisty or so loose the uterus bends over.

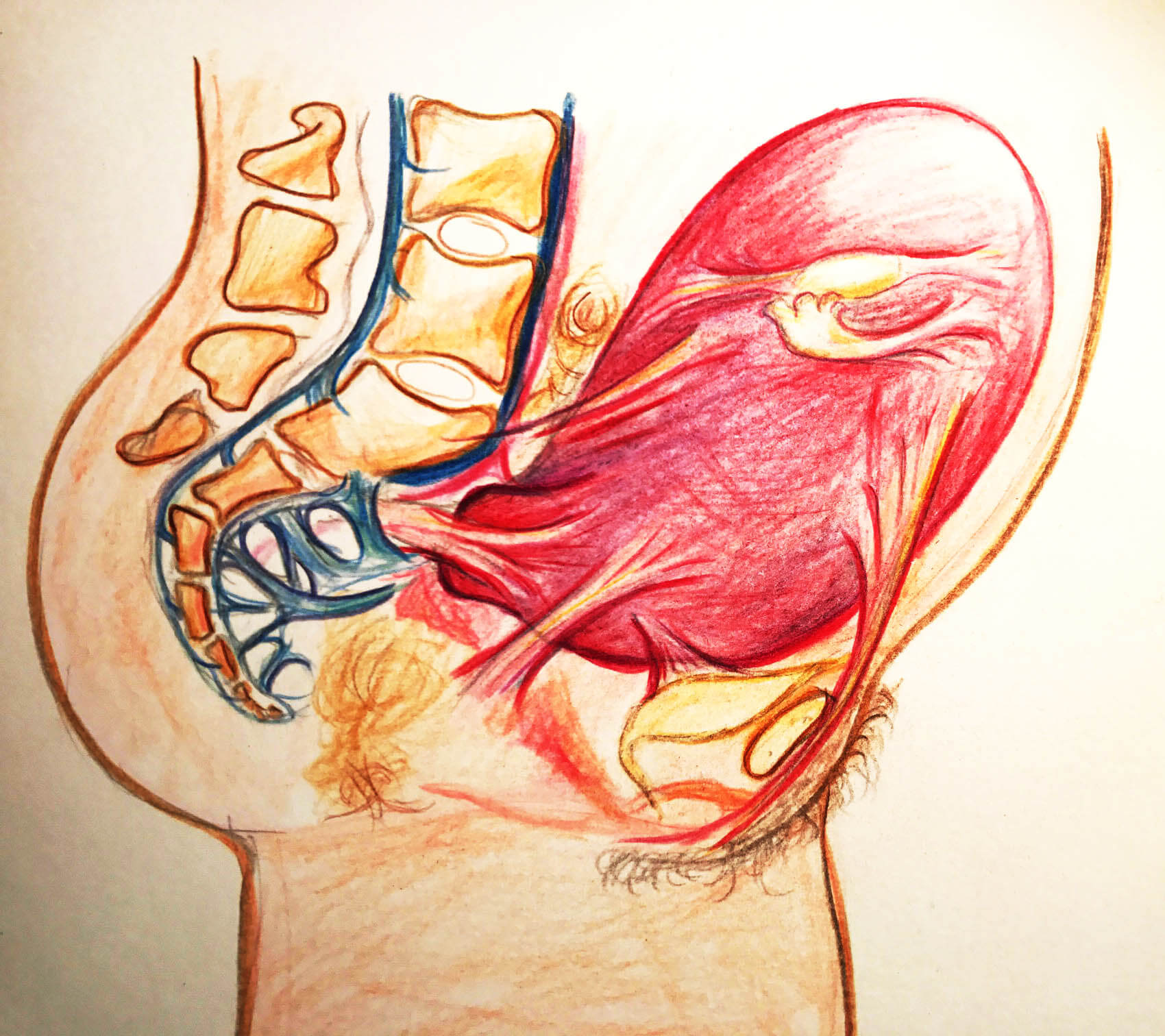

Our ability to stand depends on the psoas muscle pair. The psoas begins at T-12 vertebrae and sweeps around from the center of the sides of the spine over the pelvis to attach at the top of the thigh bone (femur). The muscle pair comes around like supporting arms, pulling up the legs so that our backs don’t fall over.

As the psoas comes across the pelvis, it makes a diagonal support for our organs. The support can be thought of as a shelf. When the uterus is large, at the end of pregnancy, a tight psoas can hold up a baby from descending and engaging in the womb. Many discomforts of the abdomen can stem from psoas tightness, but there are exercises to release the psoas. A great source is Liz Koch’s The Psoas Book.

As the psoas is balanced, so goes the birth!

So as I was saying… The Psoas.

The psoas is the lower triangle (pointing up) of two great muscle pair triangles that give core strength to the human body. The upper triangle (pointing down) is the trapezius, which is more of a diamond shape really, but I say two opposing triangles to help you to visualize of the polarity or pull between them to support our bodies.

The psoas additionally affects our pelvis and uterus because it shares the tendon connecting it to the thigh with another muscle pair, the iliacus. Together they team up to form the iliopsoas muscle group. The tone of the iliacus is dependent in part by the tone of the psoas. So, as the psoas goes, so goes the iliacus. This muscle spans from the top of the thigh (lesser trochanter) back over the pelvic brim to attach at the inside edge of the ilium (behind the hip bone but not as far to the center as the sacrum).

The pelvic floor is three layers of several muscles that rise into the lower pelvis to uplift the uterus, bladder, and other abdominal organs. The pelvic floor is open front to back to allow the urinary urethra, vagina, and rectum through to the body’s exterior. The lovely thing about the pelvic floor is the benefits of balance has far reaching benefits from better fetal positioning, easier and less painful birthing, better control and ease in peeing and pooping, walking, thinking, mood, breathing, and sexuality. Some benefits are very direct and others are secondary. A tight pelvic floor is not typically the best functioning, so beware of over kegeling. Combine the ball squeeze and anterior pelvic tilt shown in our daily activities

The pelvic floor should be considered as one unit since the three compartments work as one entity.

The uterus is pear shaped before the first birth and apple shaped for future births, Jean Sutton, New Zealand midwife describes. The uterus is shaped to support a baby in a vertical position, and head down is common due to gravity.

Some spiraling and leaning to the right is considered normal for the uterus. But too much lean is not helpful for optimal uterine functioning, including birth. These are called dextrorotation and right obliquity.

The womb is supported by a series of ropes and slings called ligaments and fascia. The ligaments of the womb have a unique mixture of fibrous tissue and muscle cells. The muscle cells allow the ligaments to become longer during pregnancy so that the ligaments can grow with the uterus. Symmetry of the ligaments helps the womb be held upright.

The cervix is part of the uterus, the part that opens for baby to be born. The cervix is pulled open by uterine contractions that first soften and thin the uterus. The cervix will be aligned properly, first aiming back in pregnancy and then, during birth, moving forward to line up with the birth canal.

Dilation is less painful when the cervix is not held to the side or back by spasming cervical ligaments. The baby’s head is better positioned with symmetrical ligaments because the lower uterine segment is not in a twist. We notice that Side-lying Release and Forward-leaning Inversion are two wonderful techniques (both from Carol Phillips) that help the uterus and baby line up with the cervix so it may open with less time and effort.

The fascia is a 3D web of fibriles which are in constant movement. This web forms a membranous tissue that wraps every muscle, organ, and bone in the body. The fascia moves with the moving body but also seems to store the “memory” of an abrupt halt. Whether that sudden stop has to do with a trauma or a long-time habit of poor posture, the fascia can thicken and then pull which can, over time, pull organs and bones out of alignment or symmetry. The function of the fascia in balance can be the most important contribution to overall health.

Fortunately, craniosacral therapists, fascial therapists and, to a lesser degree, chiropractic adjustments, can help to release the fascia and so, bring about a greater symmetry of the body. See more at Adrienne Caldwell’s blog. She shares insights and references about the fascia in her post which also talks about scar tissues after cesarean section and how multi-directional massage may reduce obstruction in motion and health.

The fetal head is heavy in comparison to the rest of the baby’s body. The vertical positions of walking, standing and sitting help the heavy head settle lower than the body during the third trimester, and sometimes in the second trimester.

The fetal skull has not yet hardened and remains somewhat flexible for fitting through the pelvis. There are plates of bone and cartilage that are nearly finished coming together at birth. That nearly finished margin is what allows molding. These margins are called sutures.

The skull plates are held together by a coating for strong fascia. This membrane also wraps down the spine to the pelvis and legs. The fascia also connects to membranes that support the brain, called the tentorium cerebelli.

Which angle the head presses past, or onto, the bony pelvic passageway determines molding. When the crown of the head enters the pelvis first molding is most efficient. When a plate, rather than the margin between, or sutures, aims into the narrow part of pelvis, molding takes a long time and does less to reduce the diameter of the baby’s head. One example of this is the asynclitic baby. Second stage can take a long time and pushing can be quite strenuous when a baby is asynclitic.

The baby’s shoulders can also mold a bit for the birth process. The shoulder girdle is flexible and many times the shoulders are folded towards the chest for the actual emergence. Other times one shoulder comes out just ahead of the other in another natural variation to reduce shoulder breadth.

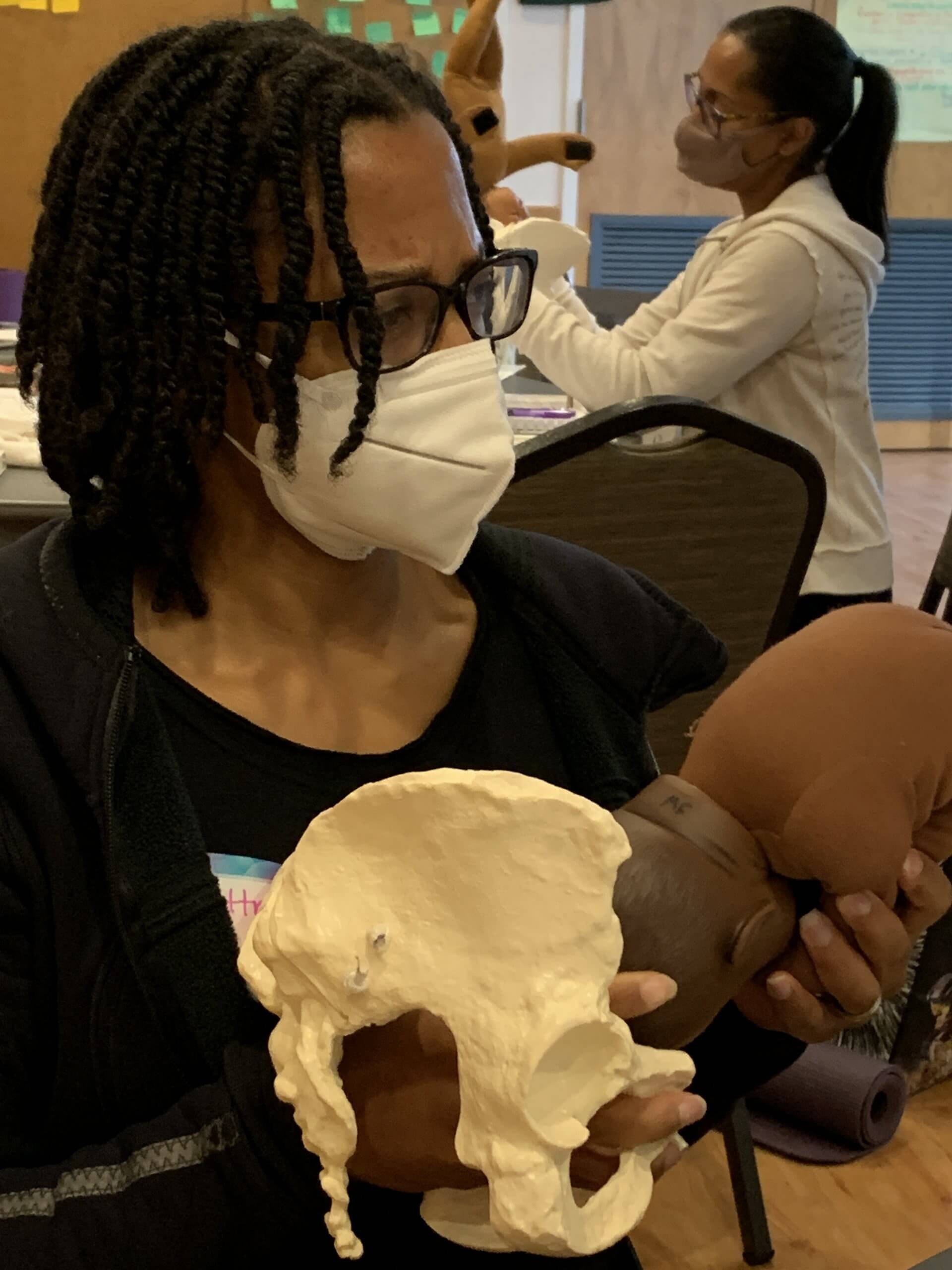

You may also like to look at Amy Hoyt’s blog posts on Optimal Fetal Positioning with explanations and photos of the pelvis and baby (doll) on her blog: Natural Birth in Kitsap.

For additional education to even further enhance your pregnancy and labor preparation, shop our extensive collection of digital downloads, videos, DVDs, workbooks, and more.